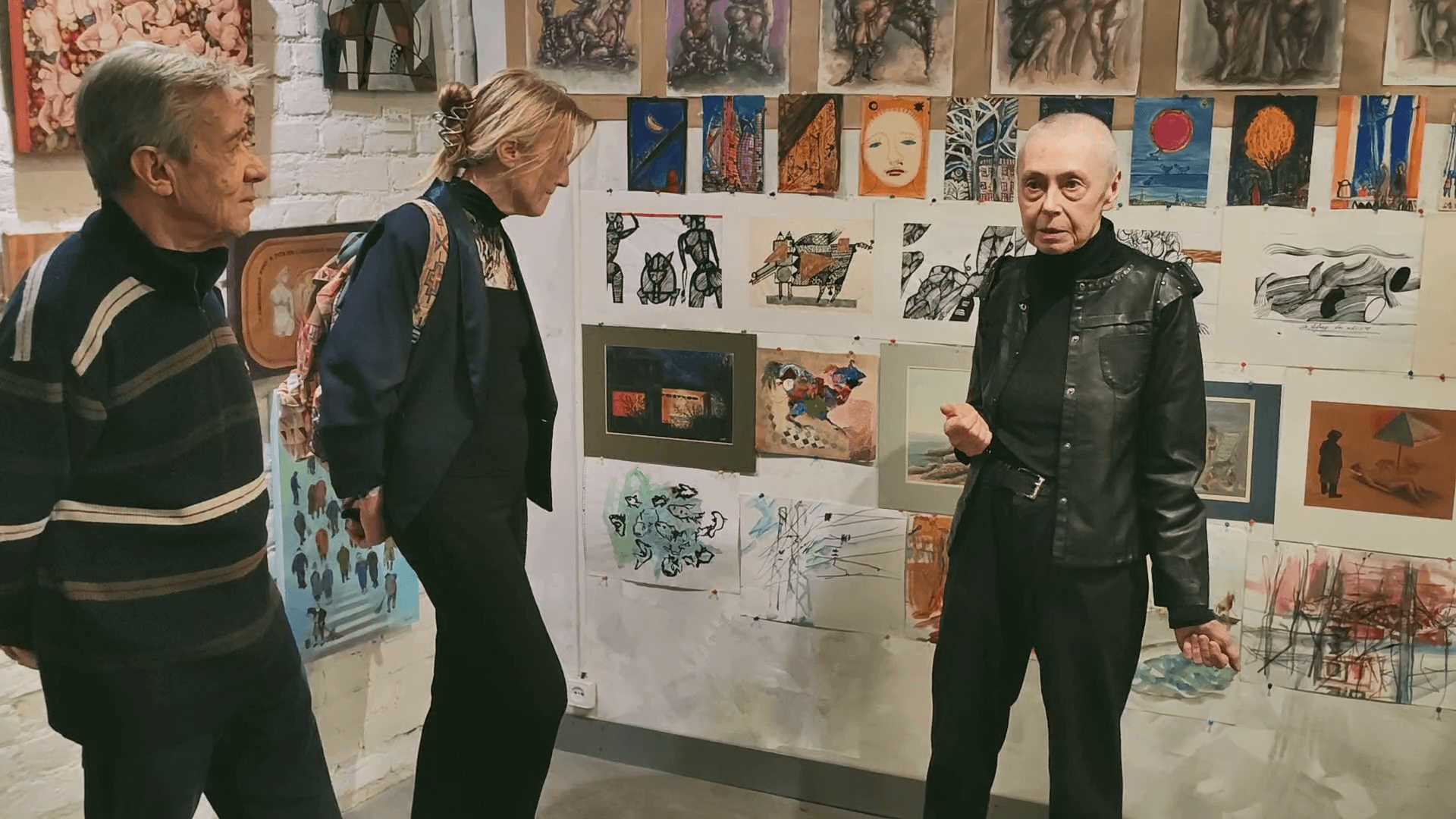

Other Artists. Three Generations

Sergey Volokhov

Tamara Zinovieva

Sergio Belo

Sergey Volokhov

Tamara Zinovieva

Sergio Belo

Concept of the Exposition

“Art Moscow” 2025

“Art Moscow” 2025

In the art of the 20th and 21st centuries, each period has seen the simultaneous existence of numerous artistic movements, making it impossible to pinpoint a single dominant mainstream. Nevertheless, certain leading trends emerge, followed by most adherents. Yet, there are always artists who do not fit into the currents of widely recognized movements, standing out in some way from the flow of art production of their era. The artists presented by the "Konosier" Gallery are precisely of this kind. As contemporaries and currently active creators, they belong to different generations, each distinguished against the backdrop of the art market of their historical period and sociocultural circumstances.

Sergey Volokhov was born in 1937.

His artistic language took shape in the 1960s and 1970s during his studies at the Pedagogical Institute named after V.I. Lenin in the Art and Graphics Department, and later through collaboration with the informal community of nonconformists. Through their art actions, they fought for the freedom of art amid the Soviet administrative and ideologically rigid artistic system. However, even within that countercultural, anti-socialist realist art, two main tendencies coexisted and competed. The first was the so-called “Second Avant-Garde,” rooted in the “formalism” of the 1920s, connected to Malevich, Kandinsky, the VKhUTEMAS school, and their followers, whose artistic principles were revived or rediscovered in the 1950s and 1960s. The second was the rising conceptual direction, which, on Russian soil, manifested as “Sots-Art.” Volokhov found himself at a crossroads between the pursuit of individual, purely plastic expressiveness in painting and graphics within the Second Avant-Garde and the expression of topical ideological-political meanings through the Sots-Art program, which essentially involved a literary selection and arrangement of visual quotes, where the expressiveness of artistic form was not an end in itself.

- “Before, I thought about how to paint, but now I realized: what to paint is what matters,” the artist said.

He chose “what,” but could not (or did not want to) abandon “how.” In this, he stands apart—both from the formalists and from Sots-Art. His arsenal of expressive means expanded, incorporating the “rough language of posters,” bluntly realistic, recognizable everyday images, material selections from objects and fragments of reality, caricatured and exaggerated imagery, and polygraphic techniques for assembling diverse materials into cohesive compositions. He mastered the postmodern collage-quotation method of creating works to perfection. Yet, each of his works is distinguished by a recognizable authorial style and evokes a powerful emotional impact through its plastic expressiveness, independent of the ideological message it carries. Political trends have shifted many times, and the relevance of the conveyed meanings is no longer perceived by contemporary audiences, but Volokhov’s “how” remains enduring.

Tamara Zinovieva (born 1954) has been drawing her entire life without holding the social status of an "artist."

Without formal art education, not being a member of the Artists' Union or a regular in nonconformist circles, she never internalized the collective normative notions about the societal purpose of art, its ideals, authorities, or other professional conventions. At the same time, from an early age, T. Zinovieva had comprehensive knowledge of art, gleaned from books, museums, exhibitions, and cultural discussions among the intelligentsia. She studied at the Department of History and Theory of Visual Arts at the Faculty of History of Moscow State University, worked as an art critic for the magazine Decorative Art of the USSR, taught visual arts at a pedagogical college, and served as an artist in an archaeological expedition. Zinovieva existed on the periphery of art, observing it from the outside, from a position of detachment. In relation to art, with its historically formed value systems and evaluative criteria—both traditional and subversive—she is different.

For T. Zinovieva, artistic activity is a natural function of the body, stemming from a kinesthetic sense. It is a form of psychomotor phenomenon known as hyperkinesis—an irresistible urge to move hands or feet aimlessly (for the pleasure of the process, stress relief, or spontaneous, childlike mischief). Equipped with a drawing tool, her involuntarily moving hand produces doodles on paper without conscious involvement, while her mind is occupied with unrelated matters. The artist’s eye associatively discerns anthropomorphic, anatomically unconventional figures in these doodles, and her periodically engaged consciousness interprets them into structures and volumes. Zinovieva’s graphic and painterly works are products of her psychophysiological activity, viewed by the artist herself outside the realm of culture, ideas, or aesthetics. They lack themes, narratives, or symbolic content. All of that is left to the viewer’s imagination—let them fantasize.

Being different in relation to the social construct called art, T. Zinovieva is not isolated from like-minded individuals. She finds kindred spirits and enthusiasts of anatomical grotesque across chronological, geographical, and organizational boundaries, dreaming of uniting them into a powerful artistic movement.

Sergio Belo is almost an adult, born in 2010.

His work fits into the current art discourse under the category of “naive”: childlike, primitive, marginal. The artistic characteristics of such art are shaped by the socio-psychological specifics of its creators. The output of untrained and exotic artistic activity, which gained recognition at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, secured a worthy place in world culture, and since then, the phenomenon has held a high rank in the art hierarchy. Contemporary aesthetics exalts the works of such artists for the mere fact of belonging to this category—lack of skill is revered as supreme mastery, naivety as profound wisdom. The high cultural status of naive art has spawned a wave of imitations and stylizations, forcing connoisseurs to discern subtle differences between genuine primitivism and its contrived counterpart.

When it comes to authenticity, Sergio Belo’s work is beyond question. He doesn’t pretend—he genuinely paints this way. Yet, within the naive art discourse, he stands apart. Contrary to the temptation to explain his art’s peculiarities through psychological factors, Sergio Belo is a normal teenager, neither a perfectionist nor a workaholic.

The nature of his art can be explained by intellectual specificity, but it is a normal specificity. In childhood, everyone exhibits thinking that generates such images and forms, but for most, this is suppressed by the subsequent development of discursive thinking, which constructs linear chains of meaning based on cause-and-effect logic: the representation of objects is replaced by description and explanation. Sergio Belo, however, retains a pre-logical, plastic intelligence—a mode of thinking in spatial forms and relationships, perceiving the world through inherently holistic images. This is an “older” intellectual norm, through which a hunter tracks prey, a farmer cultivates crops, or a craftsman creates an object—productive human activity in space without verbal instructions. For those training to become artists, awakening this plastic intelligence, often stifled by literacy and academic learning, and developing an unfragmented perception of form is challenging, and verbal explanations offer little help. Sergio Belo intuitively senses the whole. His images create a powerful effect with minimal expressive means: color patches, generalized silhouettes, simple rhythms, and the carefree, sweeping strokes of the brush. Despite their flat treatment, the figures in his paintings seem to live an independent, self-sufficient life, easily migrating from canvases to objects or incarnating as giant dolls. The characters in Sergio Belo’s visual fantasies are genuinely alive, not merely lifelike (resembling the living). He doesn’t depict them—he generates them. Looking at them, one understands how primitive animism arises—the endowment of objects, idols, and natural phenomena with life, how a savage or a child populates the world with spirits and fairy-tale creatures.

Plastic intelligence is a rare and valuable cognitive quality. Under favorable conditions, it can evolve into significant artistic talent, propelling its possessor beyond the mainstream of naivety into the broader context of art, unbound by categories.

The works of Sergey Volokhov, Tamara Zinovieva, and Sergio Belo, brought together in a single exposition, despite their individual authorial differences, reveal a supra-stylistic and trans-historical commonality. They complement the picture of the current era’s art, which cannot be reduced to mainstream trends, whether contemporary or traditional, and expand the public’s understanding of modern art.

Dates: April 23–27, 2025

Venue: Atrium of Gostiny Dvor, Moscow

Details: For more information about the program, visit the ART MOSCOW website.

Come to witness art that speaks.